Setting the record straight on critical minerals: what are they?

What are critical minerals? What is criticality?

Three years ago, we knew exactly what critical minerals were. There were no debates or throw-away comments in articles such as, “there is no universal consensus on what critical minerals are”. The debates were concentrated on how criticality should be determined and what minerals should be on the critical minerals list of the nations that need them (hint: no, not every nation on Earth needs one). So why have we gone backwards?

The answer to that is simple, suddenly critical minerals became sexy, and multiple voices began preaching about critical minerals without actually bothering to look up the basic definition of the topic they now claim expertise in. The more mainstream critical minerals became the more convoluted the narrative, eventually leading to everyone having their very own definition of ‘critical minerals’. This is somewhat unsurprising given the state of Western society – one that cannot even define what a woman is.

So, let’s go back to the basics.

What is a critical mineral?

Geoscience Australia definition:

A critical mineral is a metallic or non-metallic element that has two characteristics:

It is essential for the functioning of our modern technologies, economies, or national security and

There is a risk that its supply chains could be disrupted.

United States definition:

The Energy Act of 2020 defined critical minerals as those that are essential to the economic or national security of the United States; have a supply chain that is vulnerable to disruption; and serve an essential function in the manufacturing of a product, the absence of which would have significant consequences for the economic or national security of the U.S.

Earlier definitions also included the caveat that critical minerals were non-fuel solids, liquids, and gases. This has slowly been phased out of government discourse and replaced with metals and minerals. No this does not mean that coal is going to weasel its way in.

Let us synthesise the basics, of what makes a mineral ‘critical’:

Essential to the functioning of modern technologies, economies and

national security

Typically ‘essential’ is tied to strategic sectors, especially those that a nation is a global leader in (e.g. semiconductors)

Disruptions of steady supply could cause significant strategic, security or economic consequences with knock-on effects on interconnected sectors

Vulnerability to supply chain disruptions

These can be due to geopolitical and political disruptions, logistical, or natural, however, the monopolisation of supply chains and weaponisation of critical minerals as tools of diplomacy, particularly by China, which is the biggest factor at present

Often there is a lack of or limited substitution options (e.g. very hard to substitute REEs in permanent magnets while maintaining high spec characteristics)

These two factors combined can have significant impacts on national security economic security or the strategic ambitions of a nation.

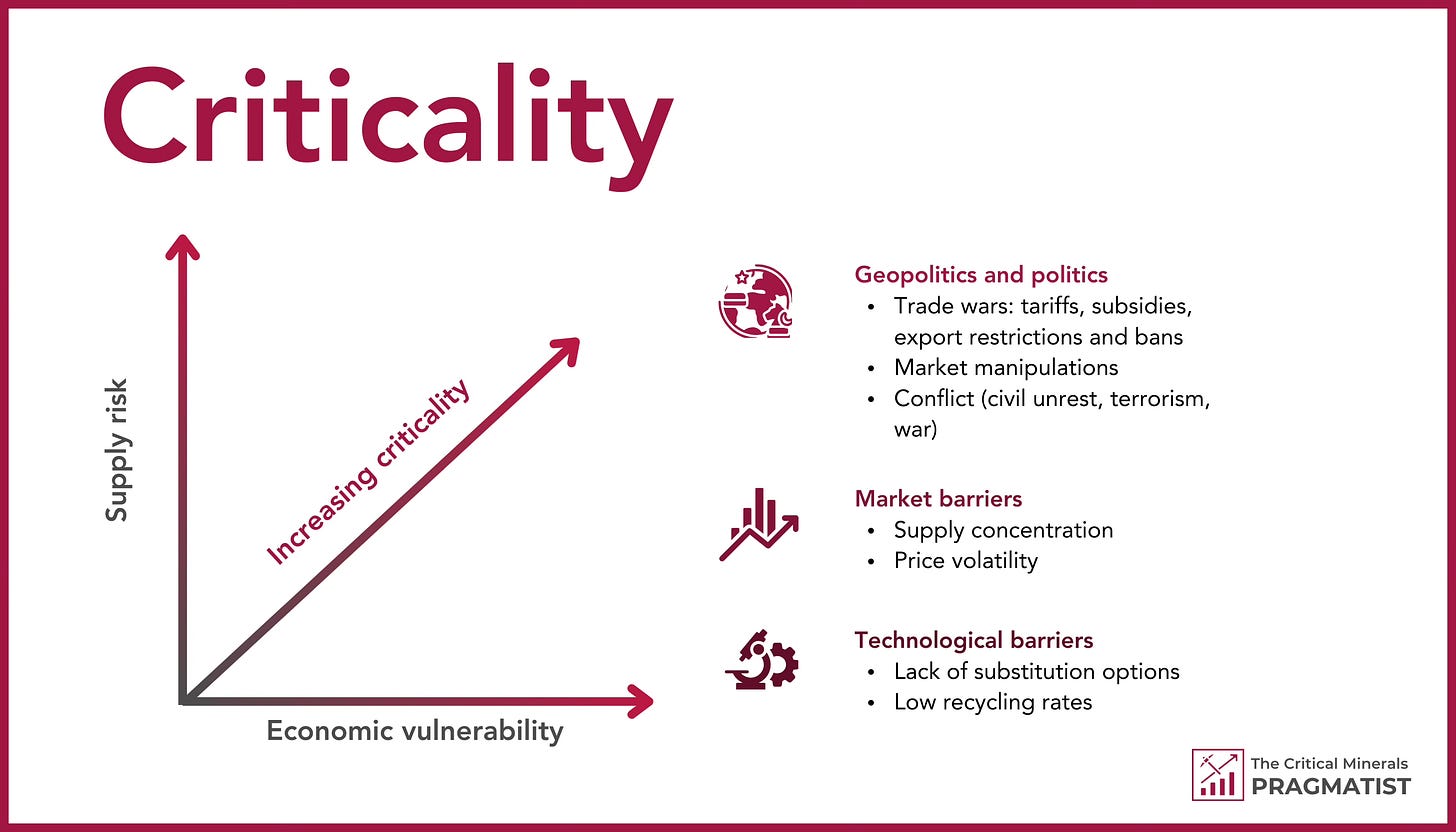

What affects ‘criticality’?

Criticality is fluid and is shaped by national goals, politics and geopolitics. For example, and at the very real risk of ending up in the Tower of London for speaking such blasphemy, if the West suddenly said “Afuera!” to net zero, battery metals might not be classed as critical. Please take deep breaths, this is just a hypothetical.

Geopolitical tensions and the weaponisation of critical minerals as tools of diplomacy are the main driving forces behind criticality at present. Especially when adversarial nations like China and Russia hold a monopoly on minerals essential to a nation’s strategic goals, the former of which is infamous for market manipulations and unfair practices.

There are four main factors affecting criticality:

Geopolitical and/or political

National goals, ambitions and strategies (economic and defence)

Trade wars, tariffs, export restrictions and/or bans (e.g. China’s decoupling from the West)

Market concentration (driven/encouraged by government(s))

Subsidies

Market manipulation (market flooding, price manipulations)

Unstable and/or adversarial regimes

Terrorism, conflict, civil unrest

Lack of strategic planning (e.g. offshoring of foundational industries)

Technological

Lack of substitution options

Low recycling rates

Limited know-how and access to processing technology

Logistical

Immature supply chains

Supply chain fragmentation

Just-in-time purchasing strategy (we know how that turned out for big auto and chips…)

Natural

Natural disasters

There are of course much smaller and nuanced factors that help to create monopolies or skew criticality, such as the Western world’s NIMBYISM (not in my backyard), feasibility (i.e. much cheaper CAPEX and OPEX in the Global South), policy and permitting regimes, investor risk appetite, etc.

The important takeaway here is that criticality is fluid, what is critical today might not be critical tomorrow as alternative supply chains form (albeit slowly).

What is the purpose of critical minerals lists?

Critical minerals lists aim to make targeted government support easier by drawing up lists of minerals that require prioritisation to meet national strategic goals. It is important to note that government strategic needs are not the same as industry or corporate strategic needs.

Creating lists is no easy task as criticality can be easily skewed by outdated and limited data (lack of transparency in China is a big issue, especially as the publicly available data has long been suspected to be altered by the CCP), as well as the context of the intended uses. Tungsten for filaments in lightbulbs is not exactly going to bring a nation to a stop, but a shortage of tungsten for artillery shells and radiation protection may have more significant implications especially amid Russia being on the EU’s doorstep…

There is also a cautionary tale, that has been lost on some governments, that too many critical minerals dilute the prioritisation of the few on which national security and technological leadership depend. This is partially due to intense lobbying efforts on behalf of think tanks and the resources industry as it pushes to have the minerals they extract listed to access extra support and funding. The industry (some, not all) is also guilty of treating “critical” as a marketing term. The irony lies in non-critical minerals creating much better returns for investors in 2023 than the critical minerals gold and coal producers are so desperate to be associated with. Hint, there is a reason why critical minerals require extra government support.

There are also competing political agendas amongst parties and government departments. The US is a good example of competing political interests. With three lists, one by the USGS boasting 50 minerals and metals, one by the Defence Logistics Agency focusing on defence needs, and one by the Department of Energy focusing on energy transition needs. Of course, all three overlap.

This is a rather controversial take, but slimmed-down lists of 10-15 minerals would be much more effective at delivering targeted support at diversifying supply chains of truly critical minerals – especially those that are crucial to major consumer jurisdictions outside of China like Japan, South Korea, the US and the EU.

The goal should not be to have a sprawling critical minerals list but to work diligently to get as many minerals off the list as possible by diversifying supply chains.

Who needs critical minerals lists and strategies?

Contrary to the chorus of LinkedIn warriors and think tanks pushing for every nation to have a critical minerals list and strategy, it is unnecessary in most nations that are neither large consumers of critical minerals nor have grand ambitions or the means to rapidly industrialise.

Some producer nations however may benefit from strategic minerals lists (more about that below) to ensure prioritisation of minerals that already create significant revenue for the nation or that there is potential for extraction.

Common misconceptions

Here’s a list of some belters:

“Silver is critical because it is needed in the energy transition.”

Cool, so is water. And so, what? Unless it meets supply vulnerability criteria for a particular consumer nation it is just a metal.

“Coal and iron ore are critical for infrastructure.”

Sure both metallurgical coal and iron ore are important for steel production and infrastructure, but the same criteria apply. The ‘critical’ in critical minerals has a very specific meaning.

“Everything is critical to some industry.”

Sure, but not all industries are critical to national security and economic edge, most importantly, not all are suffering from concentrated supply chains or unfair market practices.

“Gold is critical.”

While the Japanese and Chinese consider gold as critical, there are no immediate supply chain vulnerabilities for the Western world with diverse production across many like-minded nations. Besides, gold miners enjoy easier pathways to finance than for example rare earths or tantalum projects.

“Why don’t we just take China out of the equation and focus on the energy transition.”

You can, but good luck living in la la land.

What are strategic minerals?

This is where the grey area starts. The language has been muddled up partially due to a poor grasp of critical minerals and criticality.

Critical minerals lists support the strategic goals of a nation. So, what do strategic minerals lists support?

Logically, one would deduce a greater national security weighting and diplomatic angle applied to the so-called strategic minerals, e.g. germanium and gallium which are needed in cutting edge chips which the US wants to retain an upper hand on.

However, nations such as Australia and the EU stick minerals that don’t quite make the cut on the strategic bench, creating a B list, albeit the EU list combines both minerals for defence and the energy solution. The latter has largely arisen from lobbying efforts by industry, as the minerals deemed strategic often don’t meet the thresholds to be considered critical.

Colorado Geological Survey sums the differences up as follows.

Strategic minerals are commodities essential to national defense for which the supply during war is wholly, or in part, dependent upon sources outside the boundaries of the U.S. Because these resources would be difficult to obtain, strict measures controlling conservation and distribution are necessary. Critical minerals, on the other hand, although essential to the national defense, are less difficult to procure during wartime because they can either be produced in the U.S. or obtained in adequate quantities from reliable foreign sources. Some conservation of critical minerals may be necessary for nondefense uses. Usually a chronic domestic shortage exists for strategic minerals; potential economic reserves may or may not exist. Potential economic reserves of critical minerals may be relatively abundant, but the U.S. may rely heavily on foreign sources of raw ore simply because of economic, social, environmental, or political reasons.

The immediate issue with publicly available strategic minerals lists, if treated by their definition, is that they create a shopping and a target list for a nation’s adversary.

Why language is important

You wouldn’t call for a tricycle to be recognised as a Ferrari, so why call for coal to be a critical mineral?

While there is nothing wrong with a bit of hustle and trying to capitalise on a movement, critical minerals have a significant impact on the very foundation of the Western world, and should not be treated like the new ESG – critical minerals are not a marketing term.

Companies extracting processing or refining critical minerals require extra government support because they cannot function on a commercial basis amidst market manipulations despite providing nations with strategic benefits. Political missteps and the backing of lame horses today, or projects that only look shiny on paper, will cost future generations dearly. Governments need to be smart and deploy targeted and effective support.

Background reading:

LSE: What are ‘critical minerals’ and what is their significance for climate change action?

A good explainer and critical minerals 101. If you’re new to this space, I recommend the short read.

CSIRO: Powering the future: critical minerals explained

A good little bit of history and an Australian perspective.

Apart from the usual confusion around the definition of ‘critical’, it’s a good starter for governments looking at criticality assessments.